Primary Intraosseous Meningioma of the Calvarium a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Primary Intraosseous Osteolytic Meningioma with Ambitious Clinical Behaviour: Clinico-Pathologic Correlation and Proposed New Clinical Classification

1

Section of Neurosurgery, Ibrahim Cardiac Infirmary and Research Plant (A Eye for Cardiovascular, Neuroscience and Organ Transplant Units), Shahbag, Dhaka yard, Bangladesh

2

Department of Radiation Oncology, REM Radioterapia srl, 95029 Catania, Italian republic

3

Section of Neurosurgery, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, Shahbag, Dhaka 1000, People's republic of bangladesh

iv

Trauma Center, Gamma Knife Center, Section of Neurosurgery, Cannizzaro Hospital, 95100 Catania, Italian republic

five

Section of Neurosurgery, Highly Specialized Hospital and of National Importance "Garibaldi", 95126 Catania, Italy

6

Section of Neurosurgery, Neurosurgery Clinic, Birgunj 44300, Nepal

seven

Neurosurgery Section, James Cook University Infirmary, Middlesbrough TS4 3BW, Britain

*

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Academic Editors: Barbara Picconi and Larry D. Sanford

Received: 31 December 2021 / Revised: 16 March 2022 / Accepted: 2 April 2022 / Published: 6 April 2022

Abstract

(one) Introduction: Primary intraosseous osteolytic meningiomas (PIOM) are non-dural-based tumors predominantly presenting an osteolytic component with or without hyperostotic reactions. They are a subset of primary extradural meningiomas (PEM). In this study, nosotros present a peculiar case with a systematic literature review and suggest a new classification considering the limitations of previous classification systems. (2) Materials and Methods: Using a systematic search protocol in Google Scholar, PubMed, and Scopus databases, nosotros extracted all case studies on PIOM published from inception to December 2020. A 46-year-sometime female person patient class Dhaka, Bangladesh, was also described. The search protocol was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. (3) Results: Here, we present a 46-year-former female person patient with PIOM who successfully underwent bifrontal craniotomy and gross total removal (GTR) of the tumor. At half-dozen-month follow-upwards, no tumor recurrence was shown. Including our new instance, 55 full cases from 47 articles were included in the analysis. PIOMs were in closer frequency among males (56.iv%) and females (43.6%). The well-nigh common tumor location was the frontal and parietal calvarium, nigh normally in the frontal bone (29.ane%). Surgical resection was the predominant modality of treatment (87.3%); but one.8% of patients were treated with radiotherapy, and 5.4% received a combination of surgery and radiotherapy. Gross total resection (GTR) was achieved in 80% of cases. Extracranial extension was reported in 41.8% of cases, dural invasion in 47.3%, and recurrence in seven.3%. Whole-trunk 68 Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT has also been reported every bit a useful tool both for differential diagnosis, radiotherapy contouring, and follow-up. Current treatments such as hydroxyurea and bevacizumab take variable success rates. We have also suggested a new classification which would provide a uncomplicated common footing for further research in this field. (iv) Conclusions: Surgical resection, specially GTR, is the treatment of choice for PIOM, with a high GTR charge per unit and depression risk of complications and bloodshed. More research is needed on the differential diagnosis and specific handling of PIOM.

1. Introduction

Meningiomas are typically slow-growing tumors that arise from arachnoid cap cells [one]. Meningiomas are the nearly common principal CNS tumor and were well described in the centuries earlier Harvey Cushing coined the term in 1922 [2]. They represent 37.half-dozen% of all primary brain tumors in adults, making them the most common type of intracranial tumor with an incidence of 8.83 per 100,000 in the almost recent Central Brain Tumor Registry of the U.s.a. [3]. Risk factors include exposure to ionizing radiation such as during radiation therapy, a familial predisposition, and neurofibromatosis type ii [4,5]. In contrast, main intraosseous meningioma (PIOM) is a term used to draw a subset of extradural meningiomas that arise in bone. They represent a subtype of primary extradural meningiomas (PEM), a relatively rare entity accounting for less than ii% of all meningiomas [6,7]. They may ascend from other locations, such as the peel, orbit, nasopharynx, and neck [8,nine]. It represents approximately two-thirds of all extradural meningiomas [ten]. Peculiarly, among all PIOMs, PIOMs with both osteolytic radiological features and atypical pathological features are extremely rare. In addition, at that place are few reports almost dural interest of the PIOM [nine,11,12,13]. PIOMs are usually mistaken for primary bone tumors and appear more prone to develop malignant features compared to intracranial meningiomas [10,14,xv] Preoperatively diagnosing a scalp mass as an intraosseous meningioma is challenging, particularly when information technology is on both the calvarium and the scalp. Typical meningiomas announced as dural-based lesions isointense to gray affair on both T1- and T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and are dissimilarity-enhanced on both MRI and computed tomography (CT). As in the instance described here, preoperative diagnosis of an intraosseous meningioma of the skull is hard if imaging shows osteolysis of the inner and outer plates of the skull [14]. Recently, 68Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT has been suggested as a useful tool for the radiological confirmation of meningioma, essential for upfront gamma-knife procedures, equally well equally during follow-upwards after GK [15,16,17,18] PIOMs are very rare, and considering of their rarity, their epidemiology, natural history, clinical presentation, differential diagnosis from neuroimaging, optimal surgical strategy, and consequence are described in different case reports and series in a scattered manner. Thereby, a thorough systematic review is mandatory to sympathize the disease procedure and timely intervention to reach optimal outcomes. We present here a systematic review of PIOMs with special emphasis on their pathogenesis, machinery of osteolytic reaction, preferred location, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and future research. In addition, we advise a new classification organisation considering the limitations of previous classifications.

ii. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

We searched Google Scholar, PubMed, and Scopus databases for the selection of peer-reviewed published articles for our systematic review with advisable mesh terms. Just case reports and case series of PIOM were found. Therefore, during the selection process, we screened published case reports and case series from the inception to December 2020 post-obit the search criteria. Nosotros restricted the screening language to only English. The search terms included "primary intraosseous meningioma", "primary intraosseous osteolytic meningioma", and "PIOM" to comprise all potential articles in our analysis. The Mendeley citation manager was used for the direction of the manufactures collected through our systematic search (Effigy 1). The study is in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.

2.two. Option Criteria

To meet the objectives of our study, we included all available instance reports and case series regarding PIOM involving the skull vault and base and reviewed them meticulously. Papers defective necessary information regarding demographic characteristics, clinical presentation, diagnostic modalities, handling, histopathology, and outcome were excluded.

2.3. Data Analysis

The information from selected inquiry articles were recorded in Microsoft Excel 2013. We farther reviewed the articles for missing information and checked for consistency. Data analyses were conducted by IBM SPSS (version-23) statistical package software. (Table 1)

2.4. Example Description

ii.iv.one. Clinical History

A 46-year-old female patient was admitted to the Neurosurgery Outpatient Department of Ibrahim Cardiac Hospital and Research Institute, Dhaka, Bangladesh, in 2019, lament of a big subcutaneous mass in the frontal area. She first noticed a pocket-sized, non-tender, hard lump in the mentioned expanse eight years ago. The lesion increased very slowly over time. Two years ago, she presented a papillary carcinoma of thyroid and underwent total thyroidectomy. Due to the presence of the lesion, in that location was clinical suspicion of skull metastasis. As the patient denied any neurosurgical intervention, she was brash to receive whole-brain radiotherapy. Afterwards completion of radiotherapy, she noticed rapid enlargement of swelling, along with headaches. For the past eight months, due to additional changes in her personality and beliefs, she had an MRI of her encephalon and was referred to our department for farther evaluation and direction.

ii.iv.two. Physical Examination

Local examination of the mass demonstrated bony, hard, mildly tender swelling of 6 cm × 4 cm × 3 cm in the frontal region. The mass had ill-divers margins with an irregular surface, fixed with overlying skin besides as underlying structures. At that place were no palpable lymph nodes and no swelling elsewhere in the torso. Metastatic work-up was negative.

ii.four.3. Preoperative Imaging

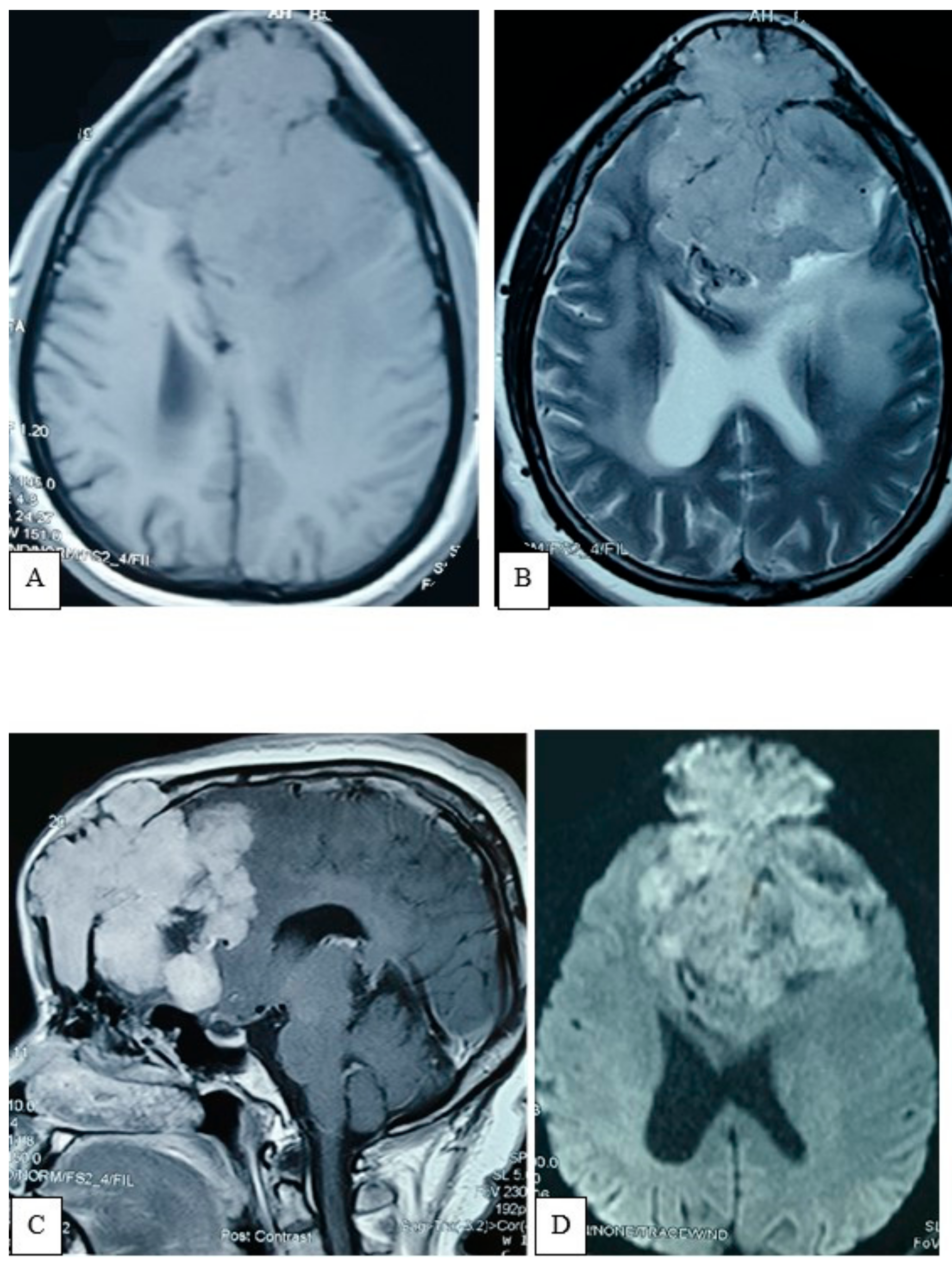

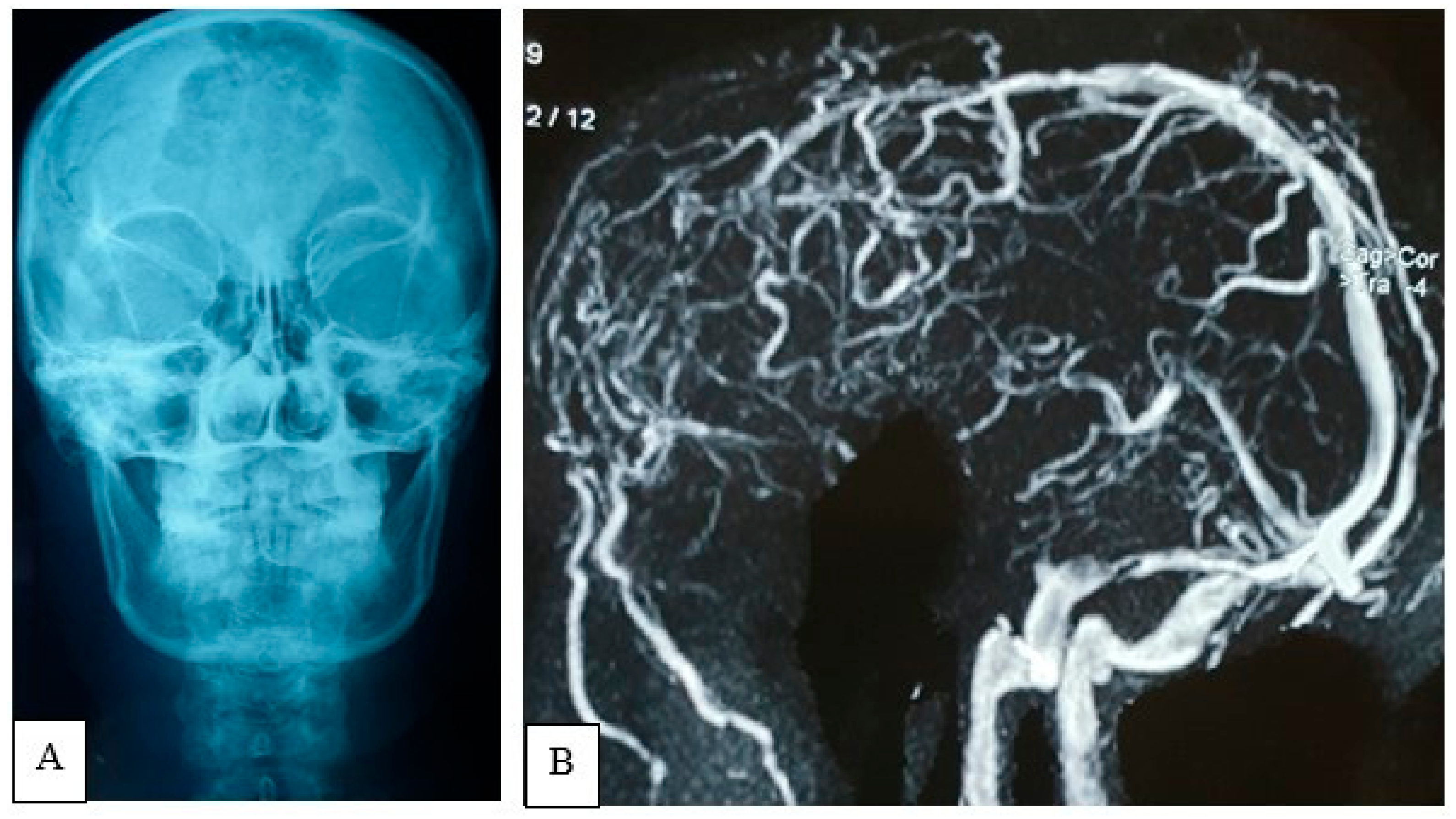

A plain X-ray of the skull showed an expansile lytic lesion having internal septations located in the frontal os, with a bulging of overlying soft tissue shadow. There was no abnormal calcification. Vascular markings appeared to be normal; all the features were suggestive of metastasis. For meliorate delineation of the pathology, an MRV was besides performed. In that location was an irregular, lobulated actress-axial T1WI iso to hypointense and T2WI heterogeneously hyperintense mass measuring about 7.9 cm × vii.6 cm × 7.four cm noted in both frontal regions (Effigy 2). Mass event was evident by pinch and displacement over both frontal lobes, sub-falcine herniation, and compression over genu and body of corpus callosum and lateral ventricles. The mass was causing devastation of the overlying frontal bone and extending into the subcutaneous region. After intravenous contrast assistants, moderate heterogenous enhancement of the lesion was observed with a central non-enhancing area, representing necrosis. MRV, post-dissimilarity sequence, showed obliteration of the anterior third of superior sagittal sinus with multiple dilated collateral vascular channels (Figure 3).

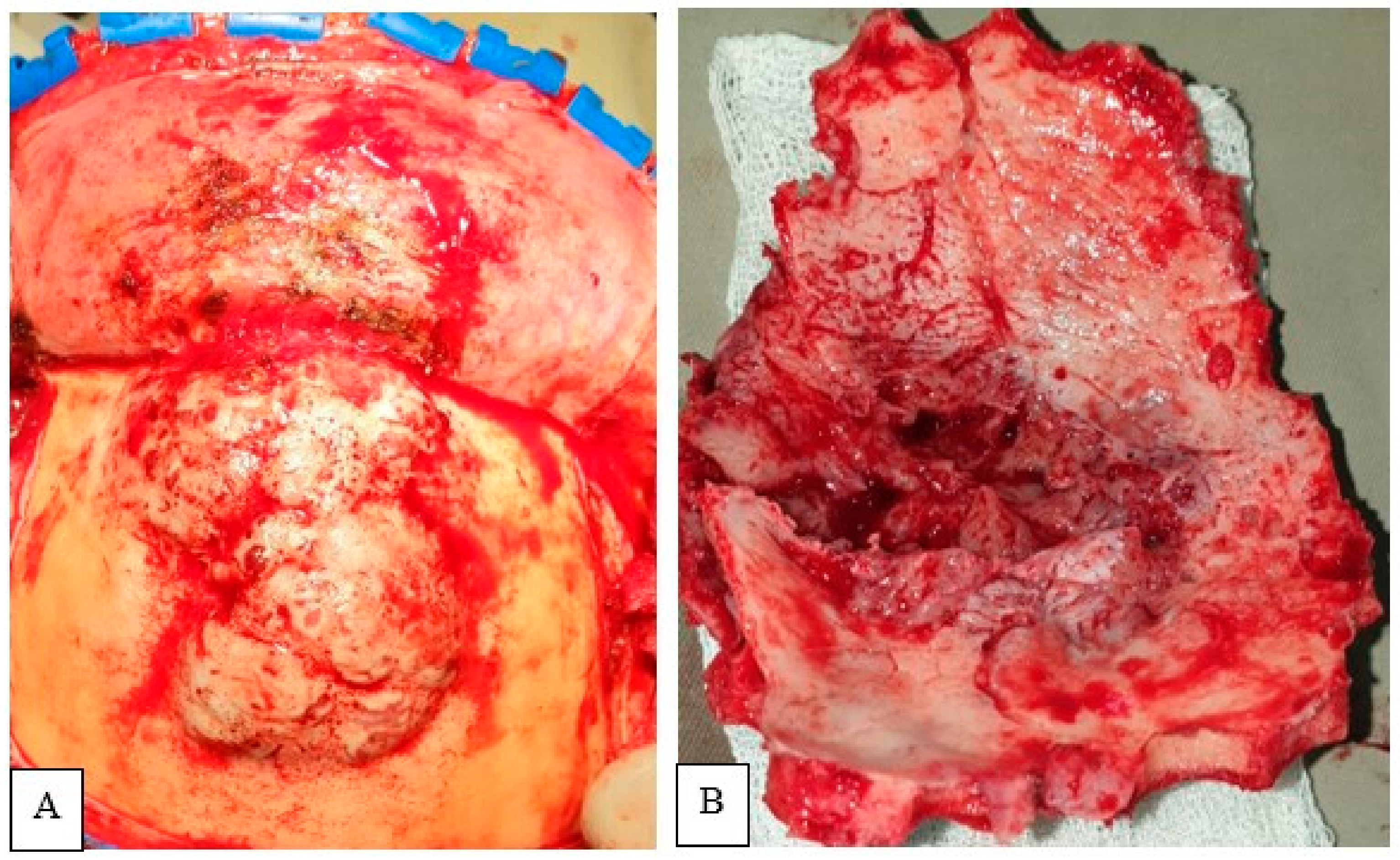

ii.iv.4. Surgical Procedure

The tumor was exposed through a bicoronal incision and subgaleal autopsy. The mass presented diffuse infiltration of the subcutaneous tissue. After meticulous autopsy, the flap was retracted antero-inferiorly (Figure 4). A bifrontal craniectomy was performed. Bone was eroded and its intracranial analogue identified. The tumor showed both extracranial and intracranial extension, with a centrally placed dural defect. The mechanical pinch of the tumor might consequence in this dural defect. Frontal sinus was occupied by the tumor tissue. With microsurgical technique, the intracranial soft tissue role was removed in a piecemeal manner. In that location was infiltration of the brain parenchyma, which was meticulously dealt with. GTR of the tumor was accomplished. After careful hemostasis, duroplasty with G-patch followed by cranioplasty with polymethyl methacrylate concluded the surgical procedure.

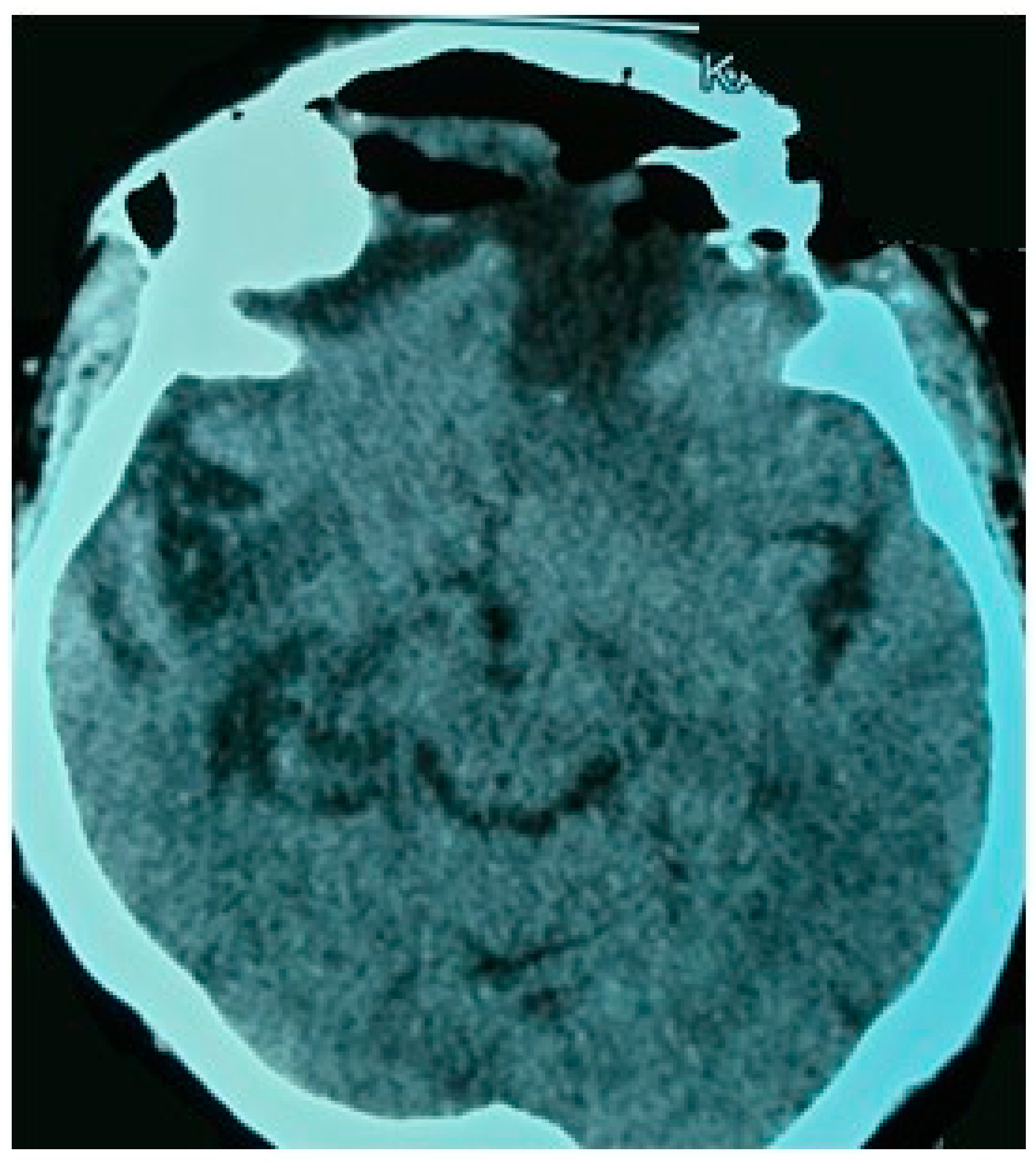

2.4.5. Mail-Operative Grade

The patient presented an uneventful recovery. There was no onset of new neurological deficits during follow-upwardly. Postal service-operative head CT scan documented a complete tumor removal (Figure 5). She was clinically stable at 6 months follow-upward.

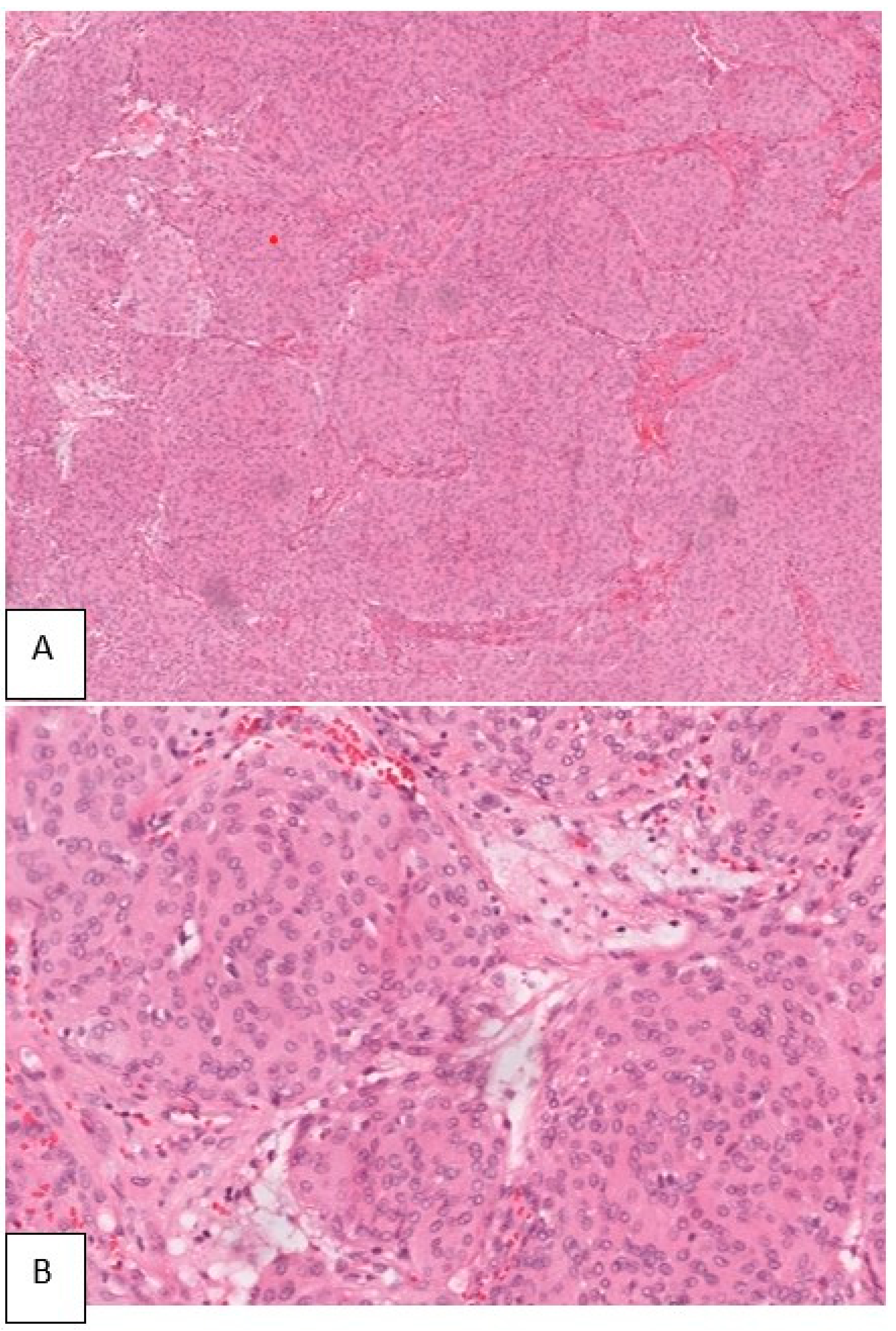

2.4.half-dozen. Histopathology

Sections made from the submitted specimen bear witness a meningothelial meningioma with whorl germination. The cells were epithelioid in shape, having oval nuclei. No mitosis or necrosis were seen (Figure 6).

3. Results

We presented a 46-year-onetime female patient treated for PIOM. Her follow-upwardly head CT scan showed GTR, and the patient was clinically stable at six months. Including our new case, a total of 55 cases from 47 articles were considered for the assay. The mean age of the study participants was 55.38 (range six–84 years); 31 out of 55 (56.4%) were males and 24 out of 55 (43.5%) were females. The near common tumor location was the frontal and parietal calvarium, with the frontal bone being the most mutual occurrence (29.1%) of the cases, the parietal os in 23.6%, and a combination of the frontoparietal os in 10.ix% of the cases. The most common symptom was a visible mass lesion, which occurred in 52.7% of the patients, and it was typically a growing mass. Surgical resection lone was the predominant modality of treatment, occurring in 87.3% of the cases. Just 1.eight% of patients were treated with radiation alone, and 5.four% received a combination of surgery and radiations. Gross total resection was achieved in 80% of cases. The mean post-operative follow-up interval was xv months. Extracranial extension was reported in 41.8% of cases and dural invasion was reported in 47.3% of cases. We categorized the PIOMs according to the histopathology following the WHO categories type I (74.5%), blazon 2 (xvi.4%), and blazon III (ix.ane%). Recurrence was reported in 7.3% of the patients.

4. Discussion

4.i. Classification of PIOM

PIOM is a term used to draw a subset of primary extradural meningioma that ascend in bone, when no dural attachment is present. They tin present either as an osteoblastic lesion or an osteolytic lesion [59]. The term "intraosseous" was used to draw those meningiomas express to skull bones with no epidural or subcutaneous components [60]. They are special subset of PEM, which has been classified by Lang et al. into three types, depending on their origin and the extent of extracranial and intracranial soft tissue interest. These are purely extra-calvarial (type I), purely calvarial (type II), and calvarial with extracalvarial extension (blazon 3) [ix].

4.2. Mechanism of Osteolysis

There are scant literature addressing the mechanism of osteolysis in PIOM. In 2007, Sade et al. showed integrin-mediated adhesion of osteoclasts to the bone matrix in the instance of skull base of operations meningioma, which promotes degradation of bone collagen by releasing lysosomal enzymes (ITG B1) [61]. Moreover, Salehi et al. demonstrated higher levels of OPN and ITG B1 expression in tumor vasculature, suggesting a vascular-dependent role. Other studies focus on the function of MMP ii with respect to brain invasion, peritumoral edema, and tumor recurrence [62]. However, the findings are still now a matter of debate.

4.3. Incidence

Although meningiomas are the most common extra-axial tumor in adults, intraosseous meningiomas are rare tumors that originate in the skull, accounting for ane–2% of all meningiomas [vi]. The majority of meningiomas are intradural, whereas primary extradural meningiomas (PEMs) originate outside the dural layer of any office of the brain or spinal string and do not have any connection to the dura mater or any intracranial structures [9]. Hoye et al. emphasized that ectopic meningiomas exercise not have any connexion with the foramina of any cranial nerves or with any intracranial structures [63]. On the other mitt, other reports demonstrated that PEM could testify intracranial growth involving the dura mater. Bassiouni et al. suggested that 14 of sixteen (88%) PEM patients who underwent surgery had a truthful dural involvement, which was proven [41]. In another report, the inner and outer dura seemed to be uninvolved by the tumor in the intraoperative finding, but a tumor infiltration to inner and outer dura was pathologically proven [64]. Thus, PIOM with "dural interest" can cause ambiguity regarding PEM, and the exact definition is all the same to be disclosed.

4.4. Clinical Presentation

Intraosseous meningiomas commonly occur in both males and females with the same frequency or with a slight predominance amidst females [41]. However, our analysis suggests dominance in males. They predominantly occur later in life, with a median patient age at diagnosis in the 5th decade, as suggested by the findings of our analysis [nine]. In our study, the most common symptom was a palpable mass lesion, which occurred in 52.7% of the patients, and it was typically a growing mass. According to previously conducted studies, the majority of intraosseous meningiomas in the base of the skull and orbit are usually asymptomatic, but may present hurting, proptosis, and neurological symptoms [13].

4.5. Neuroimaging Features and Differential Diagnosis

Co-ordinate to the literature, hyperostosis is present in 59% of PIOM imaging evidence, osteolytic changes in the surrounding os announced in 32% of cases, and mixed features of osteolysis-hyperostosis are reported in 6% of cases [14]. The bone expansion and hyperdense skull lesions may appear radiologically, e.g., en plaque meningioma, osteoma, osteosarcoma, Paget's disease, and gristly dysplasia [65]. PIOMs with osteolytic skull lesions may rarely show as hypodense bone feature outlined by a hypodense border zone [66]. These PIOMs with an osteolytic radiographic appearance may occur with a malignant behavior (progress apace and invade the surrounding structures) and show cancerous or anaplastic histopathology [66,67]. The differential diagnoses of osteolytic meningioma include metastasis and sarcoma. CTs show osteolytic hypodense lesions in metastatic conditions that thin the calvarium and erode through the inner or outer tables of the skull, sometimes associated with soft-tissue mass. Metastatic lesions or sarcoma might progress more speedily than meningioma, but information technology is difficult to make the diagnosis in this subtype before performance and biopsy [31]. 68Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT has been reported to represent a useful tool for differential diagnosis, and during follow-up to detect possible tumor recurrence. Other possible uses of 68Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT include tumor contouring for radiotherapy RT planning and subsequent follow-upwardly in which SUV modification can propose tumor control afterward RT [xv,68]. Whole-body 68 Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT has also been reported to find incidentalomas and/or extracranial meningiomas [15].

4.half-dozen. Extent of Dura and Soft Tissue Involvement

A review conducted by Lang et al. identified dural involvement in 60% (CT or MR imaging) of PIM patients. On visual inspection later craniotomy, the dura appeared normal in twoscore% of the cases [9]. Co-ordinate to our analysis, extracranial extension was reported in 41.8% of cases and dural invasion was reported in 47.3% of cases. However, Bassiouni et al. reported that 88% of patients had a true dural interest in PEMs of the cranial vault [41]. In addition, dural involvement of the PIM can exist represented with the "dural tail sign" radiologically. Although the dural tail sign generally was first idea to be pathognomonic of meningioma of the dural origin, information technology can besides exist presented by pituitary adenomas, schwannomas, and astrocytomas [9,69]. Yamazaki et al. concluded that PIMs exercise not involve the underlying dura. If the dura is involved, it is suggestive for secondary invasion of the bone [38]. After our literature review, we suggest that PIOM generally has more trend to grade a broader base in the calvarium than in the dura, while tumors of meningeal origin including meningioma take a broader base of operations in the dura than in the calvarium.

4.7. Recommended Management Strategy

Surgical resection (GTR) is the major treatment of choice for primary intraosseous meningiomas, with depression take chances of complications and mortality reported. When feasible, wide en bloc resection including 1 cm negative margins is recommended in loftier-grade meningioma [70]. In the written report by Bassiouni et al [41]., the unexpectedly loftier recurrence rate of 13.three% in tumors with benign histological features corresponds with that of 22% reported by Lang et al [ix]. and presumably due to the presence of microscopic islands of neoplasm persisting in the dura which, at the macroscopic level, had a normal advent. Therefore, we propose the removal of dura at the site of bone involvement and the subsequent undertaking of pathological cess. Wide surgical excision is the principal treatment for extradural meningiomas, and information technology is potentially curative if complete resection is accomplished [seventy]. Electric current treatments are targeting molecular pathways in the handling of meningiomas, such as hydroxyurea and bevacizumab, with variable success rates [71]. However, more research is needed for the specific treatment of PIOM. Previously, the calvarial defects were reconstructed with artificial os textile such every bit polymethyl methacrylate. Now, custom-made 3D cranial prostheses are used for their reliability, less fourth dimension consumption, and reasonable cost. Custom-made 3D cranial prostheses are also favorable in terms of their aesthetic, functional outcomes, and fewer complications [72,73].

4.8. Consequence

In our analysis, recurrence was noted in 7.iii% of cases, which is lower than another previously conducted study, where recurrence was noted in 22% of cases of benign PEMs [41]. On the other hand, a recurrence rate of 33% was reported in cases of tumors with atypical or malignant histological features [41]. Partington et al. reported that carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), which is an oncofetal glycoprotein, is associated with atypical meningioma without secretory features, and a turn down in CEA levels is associated with effective treatment of the symptomatic tumor [10].

4.9. Proposed New Classification

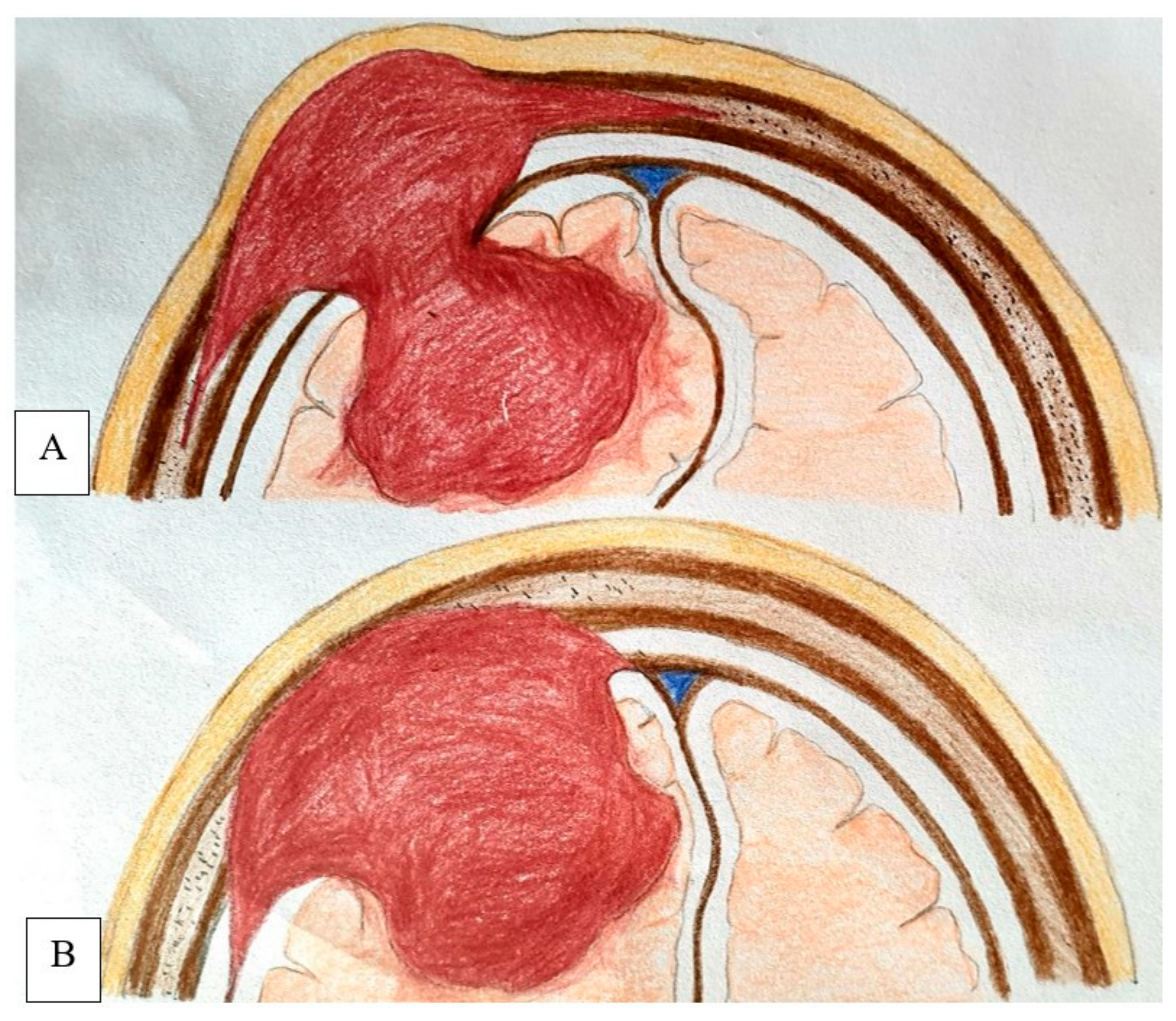

The classification past Lang et al. was unproblematic and useful from a topographical bespeak of view, merely it has some limitations [9]. Some tumor subgroups presented in instance reports cannot exist classified using the Lang Scale [41]. Some meningiomas are located between the dura mater and the inner calvarial table, master cutaneous meningiomas, and extracalvarial meningiomas fastened to the outer calvarial table [74,75]. In published cases, the inner table was disrupted in 73% of calvarial meningiomas, and some of these tumors abutted the dura. Additionally, some cutaneous meningiomas were connected to the dura through an osseous defect past a connective tissue stalk, which was shown histologically to comprise tumor cellsNone of the previous classification systems considered a tumor's involvement in the dura mater. Therefore, we included type IV (mixed variety), divers every bit tumors extending from the dura to the extracalvarial infinite. Based on the pertinent literature and on our own experience, we propose the use of this classification, which takes these differences into business relationship (Table 2) and provides a simple mutual ground for farther research in this field. This concept is demonstrated by a schematic illustration in Figure 7.

5. Conclusions

This study revealed a new case of PIOM in Bangladesh which successfully underwent bifrontal craniotomy and gross total removal (GTR). Based on our assay, we recommend consummate resection equally the treatment of choice for these PIOMs. Serial follow-up to confirm recurrence or progression should be conducted later the surgery. 68 Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT is a useful tool for differential diagnosis, RT contouring, and follow-up. The study also revealed a new nomenclature which would assist researchers and clinicians in further research in this field and in conclusion making. More inquiry is required on the machinery of osteolysis, direction strategies, and specific treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A., A.R.; methodology, G.E.U., Thou.Southward. and A.R.; software, K.H., N.A.; validation Grand.E.U., 1000.South., G.F. and B.C.; formal analysis, N.A. and M.H.; investigation, Due north.A. and A.R., resources, G.S., G.F. and G.E.U.; information curation, North.A.; writing—original draft grooming, N.A.; writing—review and editing, G.Southward., G.E.U. and A.V.; visualization, Grand.E.U.; supervision, A.R., G.Eastward.U., G.S. and B.C.; project administration, N.A.; funding acquisition, G.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This inquiry received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- NIH. Adult Central Nervous Organisation Tumors Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version [Internet]. PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. Bachelor online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26389458 (accessed on half-dozen August 2021).

- Buerki, R.A.; Horbinski, C.M.; Kruser, T.; Horowitz, P.Thousand.; James, C.D.; Lukas, R.V. An overview of meningiomas. Futur. Oncol. 2018, 14, 2161–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Cioffi, One thousand.; Gittleman, H.; Patil, N.; Waite, G.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Chief Encephalon and Other Central Nervous Organization Tumors Diagnosed in the United states of america in 2012–2016. Neuro Oncol. 2019, 21, V1–V100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferri, F.F. Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2018 Eastward-Book Ferri's Medical Solutions; Elsevier Wellness Sciences: St. Louis, MO, The states, 2017; p. 1600. [Google Scholar]

- Wiemels, J.; Wrensch, 1000.; Claus, Due east.B. Epidemiology, and etiology of meningioma. J. Neurooncol. 2010, 99, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.Thousand.; Ko, Y.; Blindside, S.S. Primary intraosseous osteolytic meningioma: A case report and review of the literature. BMC Neurol. 2019, 19, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umana, Thou.E.; Scalia, Chiliad.; Vats, A.; Pompili, G.; Barone, F.; Passanisi, M.; Graziano, F.; Maugeri, R.; Tranchina, M.G.; Cosentino, Southward.; et al. Primary Extracranial Meningiomas of the Head and Neck. Life 2021, 11, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolay, South.; De Foer, B.; Bernaerts, A.; Van Dinther, J.; Parizel, P.Grand. A case of a temporal os meningioma presenting as a serous otitis media. Acta Radiol. Short Rep. 2014, 3, 204798161455504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, F.F.; Macdonald, O.G.; Fuller, G.North.; DeMonte, F. Main extradural meningiomas: A report on nine cases and review of the literature from the era of computerized tomography scanning. J. Neurosurg. 2000, 93, 940–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.H.; Lee, Southward.K. Primary osteolytic intraosseous atypical meningioma with soft tissue and dural invasion: Report of a instance and review of literatures. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2014, 56, 509–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partington, Thou.D.; Scheithauer, B.West.; Piepgras, D.G. Carcinoembryonic antigen production associated with an osteolytic meningioma. Case report. J. Neurosurg. 1995, 82, 489–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Jung, T.Y.; Kim, I.Y.; Lee, J.K. Two cases of principal osteolytic intraosseous meningioma of the skull metastasizing to whole skull and the spine. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2012, 51, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arana, E.; Diaz, C.; Latorre, F.F.; Menor, F.; Revert, A.; Beltrán, A.; Navarro, K. Primary Intraosseous Meningiomas. Acta Radiol. 1996, 37, 937–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crea, A.; Grimod, G.; Scalia, M.; Verlotta, M.; Mazzeo, Fifty.; Rossi, G.; Mattavelli, D.; Rampinelli, 5.; Luzzi, S.; Spena, Thousand. Fronto-orbito-ethmoidal intradiploic meningiomas: A example study with systematic review. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2021, 12, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barone, F.; Inserra, F.; Scalia, G.; Ippolito, M.; Cosentino, S.; Crea, A.; Sabini, M.G.; Valastro, L.; Patti, I.V.; Mele, South.; et al. 68Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT Follow Up after Single or Hypofractionated Gamma Knife ICON Radiosurgery for Meningioma Patients. Brain Sci. 2021, xi, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, T.S.; Kleinschmidt-DeMasters, B.K.; Lillehei, Chiliad.O. Primary intraosseous meningioma: Instance report. J. Neurosurg. 1995, 83, 912–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.Y.; Shin, H.S.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, H.J. Principal Intraosseous Osteolytic Meningioma of the Skull Mimicking Scalp Mass: A Example Written report and Review of Literature. Brain Tumor Res. Treat. 2015, 3, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, E.W.; Farhat, S.M.; Hoskins, P.A.; Colvin, J.T. Radionuclide cerebral angiographic evaluation of a diploic extracranial meningioma: Case report. J. Nucl. Med. 1975, 16, 833–834. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McWhorter, J.1000.; Ghatak, North.R.; Kelly, D.L. Extracranial meningioma presenting as lytic skull lesion. Surg. Neurol. 1976, 5, 223–224. [Google Scholar]

- Palma, L.; Mercuri, S.; Ferrante, L. Epidural calvarial meningioma. Surg. Neurol. 1977, 8, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pearl, G.S.; Takei, Y.; Parent, A.D.; Boehm, Due west.M. Main intraosseous meningioma presenting as a solitary osteolytic skull lesion: Case report. Neurosurgery 1979, 4, 269–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohaegbulam, Southward.C. Ectopic epidural calvarial meningioma. Surg. Neurol. 1979, 12, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Young, P.H. Solitary Subcutaneous Meningioma Appearing as an Osteolytic Skull Defect. Due south Med. J. 1983, 76, 1039–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.H.; Tu, Y.C.; Liu, M.Y. Primary intraosseous cancerous meningioma of the skull: Case study. Neurosurgery 1988, 23, 505–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, F.; Takase, 1000.; Nishiyama, K.; Kusaka, Yard.; Morizumi, H.; Matsumoto, Yard. Written report of a instance of intraosseous meningioma. Neurol. Surg. 1988, 16, 197–202. [Google Scholar]

- Oka, K.; Hirakawa, Thousand.; Yoshida, S.; Tomonaga, M. Chief calvarial meningiomas. Surg. Neurol. 1989, 32, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammirati, M.; Mirzai, S.; Samii, M. Primary intraosseous meningiomas of the skull base. Acta Neurochir. 1990, 107, 56–sixty. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulali, A.; Ilcayto, R.; Rahmanli, P. Main calvarial ectopic meningiomas. Neurochirurgia 1991, 34, 174–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, H.; Takagi, H.; Kawano, N.; Yada, K. Primary intraosseous meningioma: Instance study. J. Neurooncol. 1992, xiii, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, T.; Nakagawa, H.; Tsuruzono, K.; Izumoto, S.; Kadota, T.; Wada, A. Extradural Temporal Meningioma Straight Extended to Cervical Bone—Case Report. Neurol. Med. Chir. 1993, 33, 458–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobashy, A.; Tobler, W. Intraosseous calvarial meningioma of the skull presenting as a lone osteolytic skull lesion: Example report and review of the literature. Acta Neurochir. 1994, 129, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzeyli, One thousand.; Duru, Due south.; Baykal, S.; Usul, H.; Ceylan, S.; Aktürk, F. Principal intraosseous meningioma of the temporal bone in an babe. A example study. Neurosurg. Rev. 1996, 19, 197–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Changhong, L.; Naiyin, C.; Yuehuan, One thousand.; Lianzhong, Z. Primary intraosseous meningiomas of the skull. Clin. Radiol. 1997, 52, 546–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukumar, N. Primary calvarial meningiomas. Br. J. Neurosurg. 1997, 11, 388–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudo, H.; Takamoto, T.; Maeda, S.; Tamaki, Northward. Intraosseous Meningioma with a Dural Defect—Case Report. Neurol. Med. Chir. 1998, 38, 229–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, Southward.; Hisaoka, M.; Aoki, T.; Kadoya, C.; Kobanawa, S.; Hashimoto, H. Intraosseous microcystic meningioma. Skelet. Radiol. 2000, 29, 354–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, T.; Tsukada, A.; Uemura, Grand.; Satou, H.; Tsuboi, K.; Olfactory organ, T. Intraosseous meningioma of the posterior fossa. Neurol. Med. Chir. 2001, 41, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosahl, Southward.K.; Mirzayan, K.J.; Samii, G.; Mooij, J.J.A. Osteolytic intra-osseous meningiomas: Illustrated review. Acta Neurochir. 2004, 146, 1245–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokgoz, N.; Oner, Y.A.; Kaymaz, M.; Ucar, K.; Yilmaz, G.; Tali, T.E. Master intraosseous meningioma: CT and MRI appearance. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2005, 26, 2053–2056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bassiouni, H.; Asgari, S.; Hübschen, U.; König, H.J.; Stolke, D. Dural involvement in chief extradural meningiomas of the cranial vault. J. Neurosurg. 2006, 105, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, V.; Ludwig, N.; Agrawal, A.; Bulsara, Thousand.R. Intraosseous intracranial meningioma. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2007, 28, 314–315. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-khawaja, D.; Murali, R.; Sindler, P. Primary calvarial meningioma. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2007, xiv, 1235–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikhrezaie, A.; Meybodi, A.T.; Hashemi, Chiliad.; Shafiee, S. Principal intraosseous osteolytic meningioma of the skull: A case report. Cases J. 2009, two, 7413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yener, U.; Bayrakli, F.; Vardereli, Eastward.; Sav, A.; Peker, Southward. Intradiploic meningioma mimicking calvarial metastasis: Case written report. Turk. Neurosurg. 2009, xix, 297–301. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, B.; Hermann, E.J.; Klein, R.; Krauss, J.Yard.; Nakamura, M. Surgical resection of osteolytic calvarial lesions: Clinicopathological features. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2010, 112, 865–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, A.; Musluman, M.; Aydin, Y. Master osteolytic intraosseous meningioma of the frontal bone. Neurol. Neurochir. Pol. 2010, 44, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhaddar, A.; Ennouali, H. Intraosseous extradural meningioma of the frontal bone. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2014, 17, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, 5.; Lam, One thousand.; Lai, A. Intraosseous meningioma mimicking a metastasis. BMJ Case Rep. 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Southward.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, H.J.; Kang, S.West.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, J.H.; Hong, S.P.; Cho, Y.S.; Choi, J.Y. Principal Benign Intraosseous Meningioma on 18F-FDG PET/CT Mimicking Malignancy. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2014, 48, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujok, J.; Bienioszek, Thousand. Microcystic Variant of an Intraosseous Meningioma in the Frontal Area: A Case Report. Instance Rep. Neurol. Med. 2014, 2014, 527267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.C.; Woon, K.; O'Keeffe, B. Brain mushroom: A case of osteolytic intraosseous meningioma with transcalvaria herniation. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2015, 29, 876–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Nsir, A.; Ben Hamouda, K.; Hammedi, F.; Kilani, M.; Hattab, North. Osteolytic clear jail cell meningioma of the petrous bone occurring 36 years later on posterior cranial fossa irradiation: Example study. Neurol. Neurochir. Pol. 2016, l, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohara, S.; Agarwal, S.; Khurana, N.; Pandey, P.North. Primary intraosseous atypical inflammatory meningioma presenting as a lytic skull lesion: Case report with review of literature. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2016, 59, 386–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouri, Chiliad.; Suzuki, H.; Hatazaki, S.; Matsubara, T.; Taki, Westward. Skull meningioma associated with intradural cyst: A example report. Clin. Med. Insights Case Rep. 2017, 10, 1179547617738231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, T.E.; Georgescu, Chiliad.M.; Kapur, P.; Hwang, H.; Barnett, S.50.; Raisanen, J.M.; Cai, C.; Hatanpaa, K.J. Unusual skull tumors with psammomatoid bodies: A diagnostic challenge. Clin. Neuropathol. 2017, 36, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuzayed, B.; Alawneh, Yard.; Al Qawasmeh, G.; Raffee, L. Clivus Intraosseous Meningioma Mimicking Chordoma. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2019, 30, e755–e757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echchikhi, M.; Habib, B.; Meriem, F.; Rachid, E.H.G.; Mohamed, J.; Najwa, Eastward.-C.E.One thousand. Primary Intraosseous Meningioma in A 60-Year-Erstwhile Patient. Int. J. Contemp. Res. Rev. 2020, 11, 20768–20770. [Google Scholar]

- Protopapa, A.South.; Vlachadis, North.; Agapitos, E.; Pitsios, T. Primary intraosseous meningioma on a calvarium from Byzantine Greece. Acta Neurochir. 2014, 156, 2379–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butscheidt, S.; Ernst, M.; Rolvien, T.; Hubert, J.; Zustin, J.; Amling, G.; Martens, T. Principal intraosseous meningioma: Clinical, histological, and differential diagnostic aspects. J. Neurosurg. 2020, 133, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sade, B.; Chahlavi, A.; Krishnaney, A.; Nagel, S.; Choi, E.; Lee, J.H. World health arrangement grades Two and III meningiomas are rare in the cranial base of operations and spine. Neurosurgery 2007, 61, 1194–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi, F.; Jalali, S.; Alkins, R.; Lee JIl Lwu, S.; Burrell, K.; Gentili, F.; Croul, Due south.; Zadeh, G. Proteins involved in regulating bone invasion in skull base meningiomas. Acta Neurochir. 2013, 155, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoye, S.J.; Hoar, C.S.; Murray, J.E. Extracranial meningioma presenting as a tumor of the neck. Am. J. Surg. 1960, 100, 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waga, South.; Kamijyo, Y.; Nishikawa, K.; Otsubo, Chiliad.; Handa, H. Extracalvarial meningiomas. Brain Nerve 1970, 22, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jayaraj, K.; Martinez, S.; Freeman, A.; Lyles, Thousand.W. Intraosseous meningioma—A mimicry of Paget's disease? J. Os Miner. Res. 2001, 16, 1154–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, J.B.; Atkinson, R.; Zee, C.S.; Chen, T.C. Chief intraosseous meningioma. Neurosurg. Focus. 2007, 23, E13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marwah, Northward.; Gupta, S.; Marwah, S.; Singh, Southward.; Kalra, R.; Arora, B. Chief intraosseous meningioma. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2008, 51, 51–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferini, One thousand.; Viola, A.; Valenti, V.; Tripoli, A.; Molino, L.; Marchese, V.A.; Illari, S.I.; Rita Borzì, K.; Prestifilippo, A.; Umana, G.Eastward.; et al. Whole Brain Irradiation or Stereotactic RadioSurgery for five or more brain metastases (WHOBI-STER): A prospective comparative report of neurocognitive outcomes, level of autonomy in daily activities and quality of life. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 2021, 32, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guermazi, A.; Lafitte, F.; Miaux, Y.; Adem, C.; Bonneville, J.F.; Chiras, J. The dural tail sign—Beyond meningioma. Clin. Radiol. 2005, 60, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattox, A.; Hughes, B.; Oleson, J.; Reardon, D.; McLendon, R.; Adamson, C. Treatment recommendations for main extradural meningiomas. Cancer 2011, 117, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Kshettry, V.R.; Selman, W.R.; Bambakidis, North.C. Peritumoral brain edema in intracranial meningiomas: The emergence of vascular endothelial growth factor-directed therapy. Neurosurg. Focus. 2013, 35, E2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosameldin, A.; Osman, A.; Hussein, M.; Gomaa, A.F.; Abdellatif, Yard. Three-dimensional custom-made PEEK cranioplasty. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2021, 12, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maugeri, R.; Giammalva, Thou.R.; Graziano, F.; Iacopino, D.M. May Autologue Fibrin Glue Lone Enhance Ossification? An Unexpected Spinal Fusion. Globe Neurosurg. 2016, 95, 611–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayhurst, C.; Mcmurtrie, A.; Brydon, H.L.; Langmoen, I.A.; Goel, A. Cutaneous meningioma of the scalp. Acta Neurochir. 2004, 146, 1383–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, T.; Mihara, Chiliad.; Hagari, Y.; Shimao, S. Primary cutaneous meningioma on the scalp: Study of two siblings. J. Dermatol. 1995, 22, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Effigy 1. PRISMA flow diagram for study selection.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram for report option.

Figure 2. Brain MRI demonstrates a T1WI iso to hypointense (A) and T2WI heterogeneously hyperintense (B) mass present in both frontal regions, having extra-calvarial and intradural extension and invasion of the brain parenchyma. Moderate perilesional edema and gross midline shifting are seen. Post-contrast, sagittal (C) and DWI (D) section demonstrates moderate heterogenous contrast enhancement with fundamental non enhancing expanse, representing necrosis. Broad base attachment lies within the diploic space. Mass result is evident by the compression over corpus callosum and frontal horn of both lateral ventricles. Restricted improvidence nowadays in scattered areas inside the tumor.

Figure 2. Brain MRI demonstrates a T1WI iso to hypointense (A) and T2WI heterogeneously hyperintense (B) mass present in both frontal regions, having extra-calvarial and intradural extension and invasion of the brain parenchyma. Moderate perilesional edema and gross midline shifting are seen. Post-contrast, sagittal (C) and DWI (D) section demonstrates moderate heterogenous contrast enhancement with central non enhancing area, representing necrosis. Broad base attachment lies within the diploic space. Mass outcome is evident past the compression over corpus callosum and frontal horn of both lateral ventricles. Restricted improvidence present in scattered areas within the tumor.

Figure iii. Patently X-ray of the skull, AP view (A) showing expansile lytic lesion with internal septation is noted within frontal bone. MRV (B) oblique view demonstrates inductive third of the SSS obliterated with multiple abnormal collaterals.

Figure iii. Plain X-ray of the skull, AP view (A) showing expansile lytic lesion with internal septation is noted inside frontal bone. MRV (B) oblique view demonstrates inductive third of the SSS obliterated with multiple aberrant collaterals.

Figure four. Intraoperative photo showing evidence osteolysis with infiltration of overlying subcutaneous tissue (A,B).

Figure 4. Intraoperative photograph showing evidence osteolysis with infiltration of overlying subcutaneous tissue (A,B).

Figure v. Mail-operative brain CT scan: axial section demonstrates gross full resection of tumor.

Figure 5. Postal service-operative brain CT scan: axial department demonstrates gross total resection of tumor.

Figure six. Photomicrograph of the biopsy specimen showing the tumor cells arranged in lobular configuration (H&Due east 40×) (A). Cells having circular nuclei with ill-defined cytoplasm. Infiltration of surrounding bone present (H&Due east 100×) (B).

Figure half dozen. Photomicrograph of the biopsy specimen showing the tumor cells arranged in lobular configuration (H&E twoscore×) (A). Cells having round nuclei with ill-defined cytoplasm. Infiltration of surrounding bone present (H&E 100×) (B).

Figure vii. Schematic analogy demonstrates the mode of intracranial extension in PIOM, where the tumor broad base lies inside the diploic space, erodes the dura, and invades the encephalon parenchyma (A) and typical convexity meningioma with extension into overlying bone whereas the broad base lies forth the dura (B).

Figure 7. Schematic illustration demonstrates the fashion of intracranial extension in PIOM, where the tumor broad base lies within the diploic space, erodes the dura, and invades the brain parenchyma (A) and typical convexity meningioma with extension into overlying os whereas the broad base of operations lies forth the dura (B).

Tabular array one. Existing cases of primary intraosseous osteolytic meningioma (PIOM).

Table 1. Existing cases of primary intraosseous osteolytic meningioma (PIOM).

| Author | Yr | Age | Sexual activity | Location | Clinical Presentation | Scalp Mass | Extracranial Extension | Dural Invasion | Mx | WHO Grade (Hist) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Klein et al. [19] | 1975 | 66 | F | P | Scalp mass | aye | aye | yeah | GTR | 1 | Not mentioned |

| McWhorter et al. [20] | 1976 | 42 | K | T | Scalp mass | yeah | yep | no | GTR | 1 | Non mentioned |

| Palma et al. [21] | 1977 | 18 | K | Fr | Intracranial hypertension | no | no | no | NA | 1 | Not mentioned |

| Pearl et al. [22] | 1979 | 44 | F | Fr | Headache, dizziness | no | no | no | GTR | i | No recurrence at iii months F/U CT |

| Ohaegbulam [23] | 1979 | 31 | M | Fr | Scalp mass | aye | no | yes | NA | ane | NA |

| Immature [24] | 1983 | 71 | M | Fr | Scalp mass | yes | no | no | GTR | 1 | No recurrence at 6 months |

| Lee et al. [25] | 1988 | 61 | Grand | Fr, T | Scalp mass | yes | aye | yes | GTR, RT | 3 | Recurrence after 2 years, no metastasis |

| Kaneko et al. [26] | 1988 | 71 | F | FP | Scalp mass | aye | no | yes | GTR | one | NA |

| Oka et al. [27] | 1989 | 79 | F | FP | Scalp mass | yep | yes | no | GTR | 1 | No recurrence later iv year and 9 months |

| Ammirati et al. [28] | 1990 | 21 | 1000 | T | Facial weakness | no | aye | aye | GTR | ane | No recurrence at 13 months F/U |

| Kulali et al. [29] | 1991 | 50 | M | O | Scalp mass | yes | no | no | GTR | ane | No recurrence at ii years F/U |

| Ito et al. [30] | 1992 | 72 | F | FP | Scalp mass | yes | no | no | GTR | ane | Not mentioned |

| Fujita et al. [31] | 1993 | 42 | M | TP | Facial weakness, hearing difficulty | no | aye | yes | STR, RT | three | Patient died afterward 1 year due to respiratory failure following metastasis |

| Ghobashy and Tobler [32] | 1994 | 65 | F | Fr | Headache | no | no | no | GTR | 1 | No recurrence at 2 years F/U |

| Partington et al. [11] | 1995 | 84 | F | FT | Scalp mass, aphasia | yes | aye | aye | GTR, RT | 2 | No recurrence after 8 months |

| Kuzeyli et al. [33] | 1996 | 6 | Thousand | T | Scalp mass | yes | no | no | GTR | 1 | Not mentioned |

| Changhong et al. [34] | 1997 | 42 | F | O | Scalp mass | yes | no | no | NM | 3 | Not mentioned |

| Muthukumar [35] | 1997 | 55 | M | P | Scalp mass | yes | yes | no | GTR | 1 | Not mentioned |

| 50 | K | TP | Personality modify, aphasia | no | yes | no | GTR | 1 | Patient lost F/U | ||

| 65 | M | Fr | Scalp mass | yeah | yes | no | GTR | i | Not mentioned | ||

| Kudo et al. [36] | 1998 | 56 | F | P | Vertigo | no | no | yes | GTR | 1 | Non mentioned |

| Okamoto et al. [37] | 2000 | 78 | F | P | H/A | no | no | no | GTR | 1 | No recurrence afterwards eighteen months F/U |

| Lang et al. [9] | 2000 | 59 | Yard | SW | Scalp mass | yep | aye | yep | GTR | ii | Non mentioned |

| Yamazaki et al. [38] | 2001 | 62 | M | O | Airsickness, nystagmus, dysmetria | no | no | yes | GTR | 1 | No recurrence after 18 months F/U |

| Rosahl et al. [39] | 2004 | 38 | Thou | T | Acute hearing loss | no | no | no | GTR | 1 | Uneventful recovery |

| Tokgoz et al. [40] | 2005 | 44 | G | FT | Scalp mass | yes | yes | no | GTR | 2 | No recurrence later on ane year F/U |

| Bassiouni et al. [41] | 2006 | 62 | F | Fr | Not mentioned | no | no | yes | GTR | 2 | Non mentioned |

| 2006 | 47 | G | P | Not mentioned | no | no | yes | GTR | 1 | Not mentioned | |

| 2006 | 46 | F | T | Non mentioned | no | no | no | GTR | 1 | Recurrence after three years F/U | |

| 2006 | 34 | M | T | Not mentioned | no | aye | aye | GTR | 1 | Not mentioned | |

| 2006 | 57 | F | P | Non mentioned | no | no | yep | GTR | one | Non mentioned | |

| Agrawal et al. [42] | 2007 | seventy | F | Fr | Scalp mass | yes | no | yes | NTR | i | No evidence of resurrection after 4 months, dural enhancement recorded |

| Al-Khawaja et al. [43] | 2007 | 50 | 1000 | P | H/A, scalp mass | yep | no | yes | GTR | one | Uneventful recovery |

| Sheikhrezaie et al. [44] | 2009 | 62 | G | FP | Scalp mass | yeah | no | no | GTR | 1 | Not mentioned |

| Yener et al. [45] | 2009 | 78 | M | P | Asymptomatic | no | no | no | GTR | 1 | Uneventful recovery |

| Hong et al. [46] | 2010 | 52 | Grand | P | Asymptomatic | no | no | no | GTR | 1 | No residue at mail service-operative CT scan |

| 2010 | 73 | Yard | O | Scalp mass | yep | no | no | GTR | iii | No residual at post-operative CT scan | |

| Yilmaz et al. [47] | 2010 | 41 | 1000 | Fr | Scalp mass | yes | no | yes | GTR | 1 | Non mentioned |

| Kim et al. [12] | 2012 | 68 | 1000 | P | Scalp mass | yes | yep | yes | GTR | 2 | Recurrence at multiple sites of whole skull after 1 year F/U |

| 74 | F | Fr | Scalp mass | yep | yes | yes | GTR | 3 | Recurrence later 19 months and 45 months F/U, underwent 2 times surgery. Later 5 years, documented metastasis. | ||

| Akhaddar and Ennouali [48] | 2014 | 37 | F | Fr | Headache, scalp mass | yes | yes | no | GTR | 1 | No recurrence after 1 yr F/U |

| Tang et al. [49] | 2014 | 82 | F | P | Gait difficulty, memory impairment | no | no | no | Biopsy | ane | Not mentioned |

| Yun and Lee [ten] | 2014 | 65 | F | Fr | Scalp mass | yep | yes | yes | GTR | 2 | No recurrence after 6 months F/U |

| Kim et al. [fifty] | 2014 | 44 | F | SW | Headache, proptosis | no | yes | no | GTR | 1 | No recurrence subsequently half-dozen months F/U |

| Bujok and Bienioszek [51] | 2014 | 59 | F | Fr | Headache, memory impairment | no | no | yeah | GTR | 1 | Uneventful recovery |

| Kwon et al. [vi] | 2015 | 69 | 1000 | P | Scalp mass, headache | yes | yep | yes | GTR | 1 | No recurrence after 6 months F/U |

| Hong et al. [52] | 2015 | 61 | Thou | FP | Headache, upper limb weakness | no | no | no | GTR | 1 | No recurrence subsequently one month F/U |

| Ben Nsir et al. [53] | 2016 | 42 | Grand | T | Hearing difficulty, facial asymmetry, vertigo | no | yes | no | IMRT | 2 | No new deficit afterwards 8 months F/U |

| Bohara et al. [54] | 2016 | 38 | Yard | P | Scalp mass | yes | yeah | yes | GTR | 2 | No recurrence after half-dozen months F/U |

| Mouri et al. [55] | 2017 | 76 | F | Fr | Dizziness | no | no | yes | GTR | 1 | Uneventful recovery |

| Richardson et al. [56] | 2017 | 23 | K | Fr | Scalp mass | yes | no | no | GTR | i | No recurrence later on 2 years F/U |

| Kwon et al. [6] | 2019 | 80 | One thousand | T, O | Hearing loss, dizziness, rest difficulty | no | yeah | yeah | NTR | 2 | Uneventful recovery |

| Abuzayed et al. [57] | 2019 | 78 | F | Clivus | Vertigo, diplopia | no | no | no | NTR | i | Uneventful recovery |

| Echchikhi Meryem et al. [58] | 2020 | lx | F | Fr | Headache, bulge | no | no | no | GTR | ane | No mail service-operative complications |

| Present case | 2020 | 46 | F | FP | Scalp mass, personality change | yeah | yes | yep | GTR | 1 | No recurrence after six months F/U |

Table ii. Classification of chief intraosseous meningiomas.

Table 2. Classification of master intraosseous meningiomas.

| Types | Description |

|---|---|

| Type I | PIM restricted inside diploic infinite, having osteoblastic or osteolytic or mixed reaction |

| Type Ii | PIM outweigh the diploic purlieus, having extracranial or intracranial component with deportation of the surrounding structures |

| Type Iii | PIM outweigh the diploic boundary, having extracranial or intracranial component with invasion of the surrounding construction |

| Blazon IV | Any of the higher up criteria with documented features of metastasis |

| Publisher's Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access commodity distributed nether the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/2075-1729/12/4/548/htm

0 Response to "Primary Intraosseous Meningioma of the Calvarium a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis"

Postar um comentário